In the age of Amazon and Alibaba, revenues generated from B2C e-sales continue to go through the digital ceiling. Customers have long grown used to order pizza and the latest iPhone online, the same goes for the routine issues with shopping 2.0. And no, I am not referring to troubles with misdirected and damaged packages or the inevitable rise of delivery drones. In fact, I am alluding to a rather different (IT-specific) problem called geo-blocking.

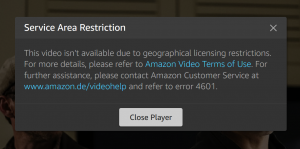

Users of online streaming services will, at some point, undoubtedly have encountered the following message in its various shapes and forms:

Said „restriction“, here in the case of Amazon Prime Video (citing the subjectiveness of its content to „geographical variability“), fits the usual definition of geo-blocking: accordingly, the term encompasses situations

Said „restriction“, here in the case of Amazon Prime Video (citing the subjectiveness of its content to „geographical variability“), fits the usual definition of geo-blocking: accordingly, the term encompasses situations

[…] where traders operating in one Member state block or limit access to their online interfaces, such as websites and apps, by customers from other Member States wishing to engage in cross-border transactions.

The definition at hand originates from a legislative act passed by the European Parliament in Strasbourg last week. Still awaiting formal approval by the Council (i.e. the ministerial body not to be confused with the „European Council“) as stated in Article 294 § 4 of the Lisbon Treaty (TFEU), the aptly abbreviated „geo-blocking regulation“ is expected to enter into force by the end of 2018 – to be precise, 9 months after its publication (Art. 11 § 1 of the proposal, hereafter GeoR).

As the name suggests, it is aimed at counteracting unjustified differential treatment based on geographical criteria attributed to EU citizens – nationality, residence, place of establishment – and regarding access to Internet services at cost (Art. 1 § 1 GeoR). The regulation is part of a wider political agenda adopted by the European Commission, namely to promote a Digital Single Market (also in the field of copyright and tax law). In return, the following remarks try to carry out an agenda of their own: first, a glance at both wording and intent of the GeoR’s components (I); second, some brief considerations on the effects of the new law in praxi (II).

I. Content: What’s (not) the matter?

Reading EU legislation can be a nuisance, courtesy of lengthy provisions with an almost casuistic touch – let alone preambles of epic proportions (called recitals). With 43 recitals and 11 articles, the GeoR is not much of an exception, partly because preceding legislation on consumer protection had to be amended (Art. 10 GeoR).

1. Scope

As sketched before, the GeoR concerns B2C relationships between a content provider (trader) and the end user of the online service provided (customer). It operates within the greater framework of anti-discriminatory EU law: on the one hand, it serves as lex specialis to Art. 20 § 2 of Directive 2006/123/EC in determining „objective criteria“ for justified geo-blocking (Art. 1 § 7 GeoR). On the other hand, the freedom to deliver goods (Art. 34 TFEU) and services (Art. 56 TFEU) as well as antitrust regulations (Art. 101 TFEU – prohibiting bilateral geo-blocking in the form of company agreements) are enforced in e-commerce relations.

The latter has been a point of contention for critics who have not hesitated to declare an „end to private autonomy“ (see this German statement) in long-distance trade. Yet: if a common European market is to fully succeed, it requires legal unity and equality of cross-border digital transactions – notwithstanding singular deviations due to logistics etc. Furthermore, there are notable exceptions to the scope laid out in Art. 1 §§ 3, 5 GeoR:

- Financial services (banking, insurance and so forth)

- Communication services (e.g. pay newspapers )

- Transport services

- Healthcare and housing services

- Gambling (e.g. lotteries)

- Audiovisual services (e.g. Video on Demand, TV or radio broadcasting).

Clearly, that ultimate aspect allows for the aforementioned „geographical variability“ of streaming content to remain a valid cause. Hence, the right to reproduce and distribute copyright-protected material (see Directive 2001/29/EC) on a transnational level prevails over the goal of a Digital Single Market.

Entirely bad news for the lovers of binge-watching? No!

Firstly, Art. 9 § 1 GeoR contains a review clause. By the end of 2020, the Commission shall present an evaluation on how the GeoR affects the e-commerce business and can propose amendments (of applicability) on that occasion.

Secondly, the EU legislator has already codified a consumer-friendly approach to streaming last year. For temporary stays abroad in a Member State, Art. 3 of the so-called online portability regulation 2017/1128/EU – in force starting March 20th – guarantees users the same range of content without additional charge. However, this customer protection is pretty specific (for holidays, business trips etc.) and the users possibly have to make cuts in quality (e.g. SD instead of HD video resolution).

2. Obligations for traders

According to Artt. 3-5 GeoR, traders of the services specified above are forced to refrain from the following restrictions and discriminations towards their customers:

- Blocked or limited access to online interface (Art. 3) – unless necessary to comply with other EU provisions, traders must not render inaccessible their online marketplaces / e-commerce websites nor practice auto-forwarding to the „appropiate“ national version of their interface if not for the explicit consent of the customer. In any case, the trader has to provide accurate information as to why the limitation occurred. The referral to external EU law is problematic since it grants excessive margins of discretion to the trader. Aside from clear instances (i.e. felonies committed by the user), the national body competent for adequately enforcing the GeoR (Art- 7 § 1) has to come up with effective guidelines.

- Divergent terms and conditions for accessing goods/services (Art. 4) – regulations not individually negotiated with the customer may not differ on a Member state basis regarding (1) the cross-border delivery or collection of physical goods (i.e. the classic Amazon order), (2) the availability of electronically supplied services or (3) the availability of other kinds of services (e.g. car rental, ticketing agencies, hotel businesses). Again, the necessity to comply with EU law can break that scheme. Moreover, sales that are subject to a net book agreement are explicitly excluded. In favor of traders, non-discriminatory measures such as dynamic pricing are permitted (§ 2). The main issue of this Article concerns a rather ambiguous wording of § 1 lit. b that could perhaps relate to subsidiary offers provided by cloud services:

where the customer seeks to:(b) receive electronically supplied services from the trader, other than services the mainfeature of which is the provision of access to and use of copyright protected works or other protected subject matter, including the selling of copyright protected works or protected subject matter in an intangible form;

- Different conditions on the means of payment (Art. 5) – finally, a trader has to execute the transaction throughout the EU for the same range of paying methods given the payment has been initiated in an accepted currency.

II. Application: What’s the projected impact?

Apart from the general viewpoint that the EU legislator interferes excessively into the e-commerce sphere by advancing the „Digital Single Market“ (which has been refuted above), the GeoR can be seen as a vital, yet somehow overly complicated step.

It certainly supports a unification of legal institutes towards a Common European Private Law in a sector that – technologically speaking – enhances the future of trade in the most substantial way recognizable. Digital systems can manage an incredible amount of transactions and can therefore speed up business plans, fostering economic growth. This factual merit of e-commerce calls for regulatory boundaries by the EU to preserve the higher goals of fair competition and antitrust enforcement.

What it doesn’t call for: exponential fragmentation of legislative products impeding the very aim (i.e. coordinating a Digital Single Market) they are meant to achieve. If a pretty specific subject like geo-blocking needs two regulations not remotely exhausting the matter – on online portability and anti-discrimination – bigger issues such as a common sales law might be next to impossible to navigate! Moreover, the activity of EU bodies cannot be limited to a mere prohibition of certain practices, thus passively reacting rather than stimulating digital development. The GeoR illustrates this particular mindset: excluding a sizeable number of services, allowing for circumvention in C2C relationships, delegating the enforcement to national bodies that will probably mirror legal differences on a supposed (common) market, obscurely referring to a dozen of other regulations.

If that is what „unity in diversity“ really means, a Digital Single Market is no more than a publicity concept. For my part, I’d favor „e pluribus unum“ – not least because the range of streaming content would be so much better!

Sources / Further reading

- Proposal for a Regulation of the European Council and the European Commission on addressing geo-blocking and other forms of discrimination […] (wording adopted upon first reading, 08/02/2018).

-

Online shoppen ohne Grenzen – Europäisches Parlament billigt Vereinbarung zur Geoblocking-Verordnung (2018 JURION 374064 = German press release, 06/02/2018).

- European Ecommerce Report 2017 – Ecommerce continues to prosper in Europe, but markets grow at different speeds (Ecommerce foundation, 26/06/2017).

- Pieter van Cleynenbreugel, The European Commission’s Geo-blocking Proposals and the future of EU E-Commerce Regulation (2017 Masaryk University Journal of Law and Technology 11-1, pp. 40-62).

- Lutz Riede/ Matthias Hofer, Der Vorschlag der Geoblocking-Verordnung. Mögliche Auswirkungen für Unternehmen und Verbraucher (2017 MR-Int 14, pp. 14-21 = German publication accessible via juris).